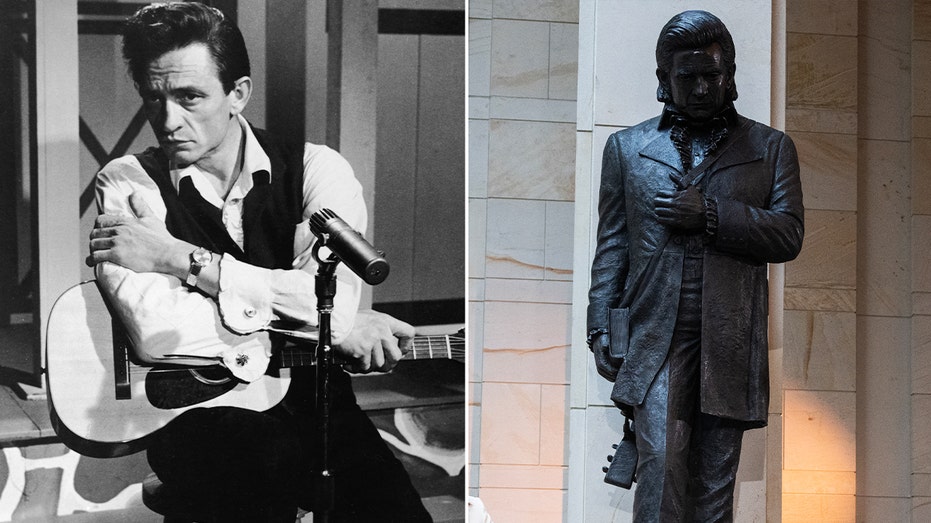

Johnny Cash has become the first musician to be honored with a statue in the U.S. Capitol, joining presidents such as Ronald Reagan and George Washington and civil rights figures such as Rosa Parks.

Statues of Presidents – ranging from George Washington to Ronald Reagan – stand in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda.

The walls of the Capitol complex are lined with inventors such as Thomas Edison of Ohio and Utah’s Philo Farnsworth – who is credited with helping create television.

There are statues of American heroes, ranging from Helen Keller to Amelia Earhart to astronaut Jack Swigart.

IN CONGRESS – LIKE BASEBALL – THERE’S ALWAYS NEXT YEAR

Religious figures pop up, including Junipero Sera from California and Father Damien of Hawaii.

Civil rights figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks are well represented.

There are even writers. Will Rogers of Oklahoma and Willa Cather of Nebraska.

But there were no musicians.

Until now.

He’s known simply as the Man in Black.

“Johnny Cash walked the line. It wasn’t a straight line. Much more like the Arkansas River. Jagged. But always moving forward,” said Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, R-Ark., at a recent dedication ceremony.

Perhaps this is an example of Congress moving forward, stretching out into the arts and pop culture.

“Some may ask the question, ‘Why would a musician have a statue here in the halls of the great American republic?’” queried House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La. “And the answer is actually pretty simple. America is about more than law and politics.”

Cash’s statue is the latest addition to the Capitol collection. Each state receives two statutes on Capitol Hill. Individual states determine who should represent them. The Arkansas state legislature voted in 2019 to swap out both of its statues. Earlier this year, officials removed the statue of Uriah Rose. He was a Confederate sympathizer and founder of the Rose Law Firm in Little Rock – associated with Hillary Clinton and other Clinton Administration figures. In exchange, they installed a statue of civil rights activist Daisy Bates. Johnny Cash’s statue takes the place of the late Sen. James Clarke, D-Ark., a segregationist.

The bronze statue practically greets you with the singer’s golden-throated, signature introduction: “Hello. I’m Johnny Cash.”

The statue features the singer clasping a Bible in his left hand. A Martin D-35 acoustic guitar is slung across Cash’s back, the neck pointed downward. He’s attired in a tuxedo shirt with ruffles. A box-back coat hangs around him like a cape. And, of course, there are cowboy boots.

Moments after they yanked the cloth off the statue to reveal Cash, his sister, Joanne Cash, approached it. Now blind, Joanne spent several moments touching and feeling the contours of the bronzed version of her brother – now memorialized for the ages.

SHOW VOTE: REPUBLICANS MAKE POLITICAL STATEMENT IN GOING AGAINST SPEAKER JOHNSON

The statue epitomized the dichotomy of Cash. A Zen-like quality. Yin and yang. Light and dark.

“He was open about straddling the border between clean cut Johnny and beaten down Cash,” said Sanders. “Johnny is the nice one. Cash causes all the trouble.”

The governor referenced Cash recording his albums at Folsom State Prison and San Quentin.

“It’s not hard to imagine that he, too, looked out at that prison crowd and saw a version of himself staring back,” said Sanders.

She added that Cash “wrote that he felt like a walking vision of death.”

Johnson observed that besides Cash, “no one else would be singing at Folsom Prison.”

Johnny Cash sang about farmers washed out by floodwaters in “Five Feet High and Rising.” Those songs seemed to be the most important in his repertoire, as he focused on the “forgotten men and women,” said Johnson.

Those were some of the most important songs in Cash’s repertoire.

Besides his “Man in Black” stage persona, darkness perpetually cloaked Johnny Cash. That rendered ruinous lyrics which would have bordered on hyperbole had they not been so resonant.

“I taught the weeping willow how to cry,” wrote Cash in Big River.

“I will let you down. I will make you hurt,” concedes Cash in Hurt.

“I fell into a burning ring of fire,” sings Cash in one of his best-known songs. “And it burns, burns, burns.”

SENATE TO SWEAR IN MENENDEZ SUCCESSOR FOLLOWING NJ LAWMAKER’S CONVICTION, RESIGNATION

Simple.

Yet mercilessly true.

“He was a Shakespeare of the South,” said Cash’s daughter and singer Rosanne Cash. “Reams and reams of poetry spilled from him. He was a flawed but profoundly humble, kind and compassionate man with a magnificent generosity of spirit.”

His daughter said that Cash “loved those who failed and made terrible mistakes, but who admitted to their God and themselves their failings because he himself knew the darkness he wrestled with his whole life.”

But despite his internal demons, Cash’s daughter said she learned a special lesson from her father.

“He said to us children many times in moments of conflict or anger, ‘Children, you can choose love or hate. I choose love,’” said Rosanne.

In fact, those words are inscribed on the concrete base of the statue for all to read.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., said Cash inspired generations of artists. He said that long before Jay-Z dropped the Black Album or Black Sabbath practically created the heavy metal genre, the Man in Black seized ownership of the hue for his own.

“Snoop Doggy Dogg put it a different way. He called Johnny Cash ‘a real American gangster,’” said Jeffries, drawing laughter. “That’s a compliment from Snoop Doggy Dogg.”

Even lawmakers recite Cash’s lyrics.

“’I can actually see the gravel in his gut and the spit in his eye,’” said Rep. Steve Womack, R-Ark., referencing Cash’s country hit A Boy Named Sue. “I loved that song. I loved it so much that I committed to memory its lyrics.”

And while many people who visit Congress have never heard of some of the people honored with Capitol statues, everyone has heard Johnny Cash.

“You’ll hear Johnny Cash on classic country. You’ll hear Johnny Cash on classic rock. You’ll hear Johnny Cash on gospel,” said Rep. Rick Crawford, R-Ark. “It’s just a testament to his ability to transcend those musical genres.”

As Johnny Cash crooned, “I’ve been everywhere.”

Now he’s been to the U.S. Capitol.

But here he’ll stay.

In permanent residence.