The Justice Department ordered the Drug Enforcement Administration to halt random searches of passengers at airports and other transit hubs after a watchdog raised concerns.

The Drug Enforcement Administration is no longer allowed to randomly search travelers at airports and other transit hubs after a scathing report from the Justice Department found “serious concerns” with the practice.

DEA agents failed to properly document searches, may have illegally targeted minorities and, in at least one case, paid an airline employee tens of thousands of dollars over several years to suggest targets for searches, according to the report released Thursday by Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz.

The deputy attorney general ordered the DEA to suspend the random searches Nov. 12 after seeing a draft of the memo.

The report refers to video of one traveler’s experience, which went viral in July when released by the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit civil rights law firm.

“I don’t consent to search, sir,” the traveler, identified as David C., tells a federal agent who is demanding to search his backpack.

“You don’t have to consent,” the agent responds in the video, recorded earlier this year. When David repeats that he doesn’t consent, the other man says, “I don’t care what [about] your consent stuff.”

David kept filming as the agent took his backpack off the plane and waited for a drug-detection dog. The agent claimed the dog alerted him to the bag. David continued refusing to allow the search, but eventually gave in. The agent didn’t find anything illegal in the backpack, but by the time the whole ordeal was over, David had missed his flight to New York.

David was singled out because he had purchased a last-minute ticket, the agent said in the video.

“We wouldn’t do this, and be doing it across the country if it wasn’t legal,” the agent can be heard saying toward the end of the recording. “It would be shut down.”

The subsequent investigation found that the DEA had been paying at least one airline employee a percentage of seized cash for several years in exchange for information about passengers who purchased tickets to certain cities within 48 hours of travel.

That airline employee received tens of thousands of dollars in kickbacks from the DEA over the years, the OIG found.

It’s likely impossible to say how many travelers have been subjected to such searches, because the OIG report notes that the DEA rarely leaves a paper trail unless the search results in a seizure or arrest.

“[The] OIG report confirms what we’ve been saying for years about predatory DEA practices at airports,” IJ Senior Attorney Dan Alban said in a statement.

A 2016 USA Today investigation found that DEA agents at 15 major airports seized more than $209 million from at least 5,200 travelers over the decade prior. Most of that money was shared with local police departments, the report found.

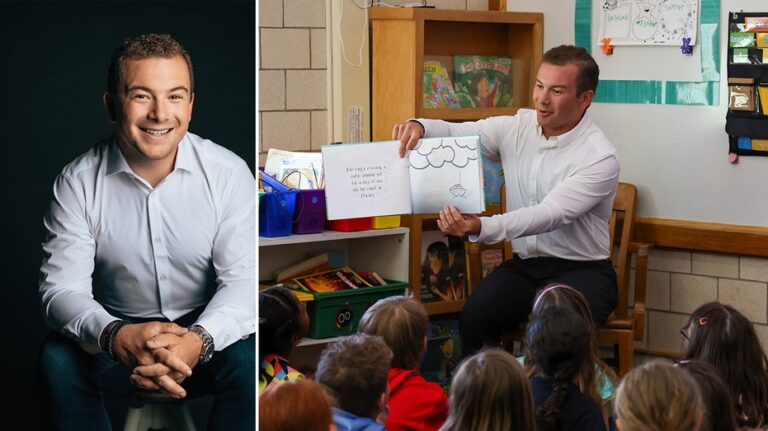

Fox News Digital previously spoke to musician Brian Moore, who had $8,500 seized while waiting at his gate at the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. Moore was never charged with a crime and got his money back after a yearlong legal battle that cost him $15,000 — nearly double the amount the DEA took.

“It was terrible, the worst experience of my life,” Moore said. “They basically, in that one day, in those few minutes, ruined my entire music career.”

THIS COUPLE LOST THEIR HOME AFTER POLICE SEIZED THEIR CASH. A JURY AWARDED THEM $1 MILLION

IJ is currently suing the DEA and TSA over their airport seizure and forfeiture practices, and advocates for legislation that would end the “profit incentive that fuels unconstitutional searches.”

“We welcome DOJ’s suspension of this program as a first step, but policy directives can be changed at any time, under this or future administrations,” Alban continued.

The Justice Department memo suspends “all consensual encounters at mass transportation facilities unless they are either connected to an existing investigation or approved by the DEA Administrator based on exigent circumstances.”

“The DEA’s failure to collect data for each consensual encounter, as required by its own policy, and its continued inability to provide us with any assessment of the success of these interdiction efforts once again raise questions about whether these transportation interdiction activities are an effective use of law enforcement resources—and leaves the DEA once again unable to provide adequate answers to those questions,” Horowitz wrote.

The report advises the DEA to rethink whether solely purchasing a last-minute plane ticket suggests criminal activity, and if agents’ practice of approaching passengers as they are trying to board a “soon-to-be departing flight could be viewed as placing undue pressure on travelers to accede to such requests.”

The DEA did not immediately respond to a request for comment on the report.

The OIG noted that DEA agents are not required to wear body cameras, making David C’s recording an “important record of the interaction.”

David was one of five passengers flagged for search that day, according to the report, although the delay he caused by initially refusing to let the agent search his bag meant agents were not able to contact all the other travelers.

None of the travelers had a “relevant criminal history” or other reason to suggest they “might be engaged in illegal activity,” the report notes.