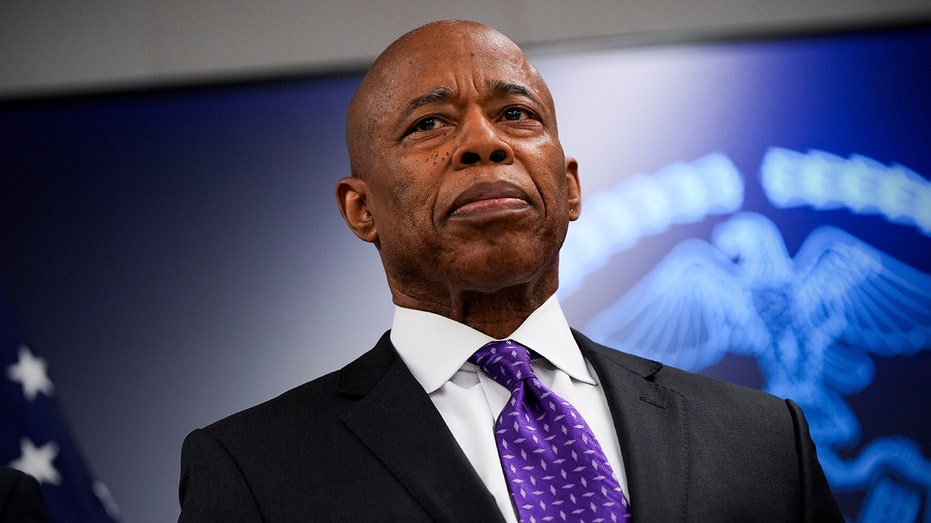

Former federal prosecutor William Shipley takes a closer look at the controversy surrounding the DOJ’s decision to drop its case against New York City Mayor Eric Adams.

Three weeks ago, the media was consumed by a firestorm that broke out when President Donald Trump’s acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Danielle Sassoon, resigned in protest over being ordered to end the prosecution of New York Mayor Eric Adams.

The acceptance of Sassoon’s indignant and public resignation was followed closely by resignations of several of her underlings in New York, as well as lawyers in the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section in Washington, all of whom objected to the dismissal the case. The motion to dismiss was eventually filed by Acting Deputy Attorney General Emil Bove.

MIKE DAVIS: TRUMP DOJ BRINGS DOWN ‘SOVEREIGN DISTRICT’ OF NEW YORK

The media extolled the “bravery” of career prosecutors who were standing up to the “corrupt” efforts by the newly installed Trump DOJ officials to reward the wayward Democrat mayor for his opposition to Biden administration immigration policies. The dismissal of charges was also alleged to be a reward, or quid pro quo, for his post-election commitment to cooperate with Trump administration’s efforts to reverse former President Biden’s open border policies.

The Biden Justice Department had indicted Adams last September on a somewhat questionable bribery charge involving an upgraded flight to Turkey. Because it came after he had voiced public criticism of Biden’s policies on illegal immigration, some supporters of Adams deemed it another example of the “weaponization” of Biden’s DOJ.

On March 3, the judge in the case noted during a hearing on the motion that because the two sides were aligned — DOJ and Adams both agreed on the propriety of the motion — there is no one to advocate the position taken by the disgruntled former prosecutors. Were their concerns and complaints valid and something the judge should consider in deciding what to do with the motion? To have those concerns addressed, the judge appointed an “amicus” counsel to advise the court on the legitimacy of the issues raised by those objecting to the dismissal. His choice, former DOJ Solicitor General Paul Clement, reviewed the motion and, on Friday, filed a brief with the court on the legal and factual issues presented.

As Clement was submitting his brief, newly confirmed Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, along with his now principal assistant deputy, Bove, filed a memorandum under their own signatures – no other DOJ officials are listed. he point of that was to make very clear that this is the position of senior DOJ management, and the views of subordinates in the chain-of-command are not relevant or necessary.

There are two interesting and distinct takeaways from the two memos. First, the DOJ is entirely correct on the law and the near complete discretion that rests with the Executive Branch when making the decision to abandon a case even after a grand jury indictment is returned. Second, the Blanche memo makes clear that the “weaponization” arguments that were offered as the basis for the dismissal are the subject of an ongoing investigation into both the investigation of Adams and the decision to charge him. This second takeaway is revealed by the fact that the memo quotes from some communications among members of the prosecution team at SDNY. It also requests that full text of those communications be placed under seal and not be filed on the public docket. Such a request indicates an ongoing investigation into the matter is underway.

As for the first takeaway, on whether the Trump DOJ have the law on their side in moving to dismiss the case, Clement’s memo makes some strained arguments to suggest a role for the court in reviewing motions to dismiss. But he knew when he started that there is simply a torrent of case law that recognizes the nearly unchecked discretion vested in the Executive Branch to make the pending motion, combined with the realization that there is no meaningful way for a court to compel the Executive Branch to prosecute a case it is determined to not prosecute.

The DOJ memo cites dozens of cases that underscore that the final decision on deciding to dismiss a case rests almost entirely with the Executive Branch. The following are just a sampling of the quotes from different cases – sans the case names for brevity – included by DOJ in its Memorandum.

Still, the Clement memo does attempt to carve out some space for the court to weigh in on the decision.

“… Rule 48(a) provides the court with an important, but limited, role in assessing the government’s motion to discontinue an ongoing prosecution,” it states. “The Rule authorizes the court to consider how the prosecution should be discontinued — with or without prejudice — rather than empowering the court to take over the distinctly executive prosecutorial function.”

Because Adams is an elected public official, Clement does recommend that the dismissal be “with prejudice,” meaning it cannot be brought again in the future. This recommendation is not anchored to any specific legal authority or case citation – Clement simply suggests that it is prudential to avoid the perception that Adams, while still mayor, might be influenced in his decision-making by the self-interest of avoiding the refiling of the indictment.

Contrary to some reporting and social media commentary, Clement does not reach a conclusion on the question of whether the case was initiated improperly – “weaponized” — or that the motives to dismiss the case are characterized by bad faith or an improper quid pro quo. What Clement does say is that the fact both allegations have been aired in public weighs in favor of dismissing the case since either – independent of the other – would be a basis for dismissing the indictment with prejudice.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

What these two memos underscore more than anything is the fundamental misunderstanding of the law by the now-resigned ex-prosecutors. The premise of their protest and later resignations was that they could not make a “good faith” argument to the court under Rule 48(a) that would justify dismissing the indictment. They did not recognize that other enforcement priorities of the new Trump administration might outweigh their self-righteous pursuit of the mayor the regard as a scoundrel.

But more significantly, they did not understand that every decision to prosecute or not prosecute is a trade-off against competing interests that are in play. They mistakenly – and naively – believed that an initiated prosecution based on sufficient evidence must be taken to its conclusion, and that any decision to do otherwise based on competing policy considerations must be “corrupt.”

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FROM WILLIAM SHIPLEY