A judge in a key battleground state has ruled that county election officials must certify results by the legal deadline even if they suspect fraud or mistakes.

A judge in a key battleground state has ruled that county election officials must certify results by the legal deadline even if they suspect fraud or mistakes.

Superior Court Judge Robert McBurney of Fulton County, Georgia, ruled that “no election superintendent (or member of a board of elections and registration) may refuse to certify or abstain from certifying election results under any circumstance.”

The officials do have the right to investigate their concerns about the vote count and to review related documents, McBurney wrote, but “any delay in receiving such information is not a basis for refusing to certify the election results or abstaining from doing so.”

Election results must be certified by Georgia’s individual counties by 5 p.m. the Monday or Tuesday after the race.

The ruling was handed down the same day Peach State residents head to the polls for early in-person voting, which runs from Oct. 15 through Nov. 1.

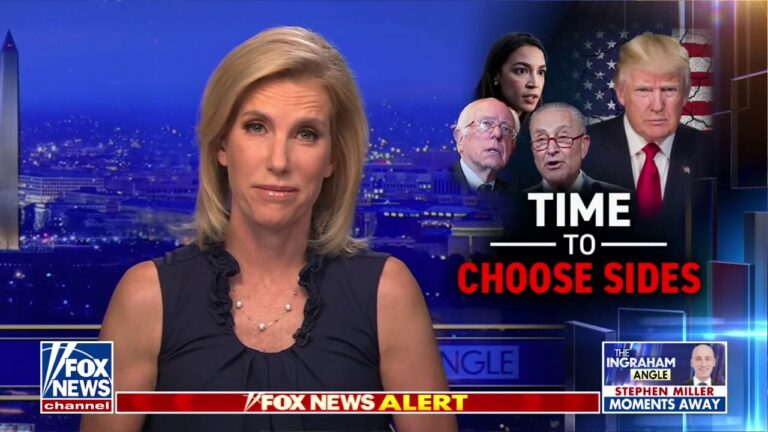

The suit was filed by Fulton County Board of Registration and Elections member Julie Adams and backed by America First Policy Institute, a conservative group aligned with former President Donald Trump.

Adams had voted against certifying the presidential primary results in May. She then sued the Fulton County elections board, arguing she was not able to fulfill her duties as a superintendent after a documents request was denied, and that she was within her rights to not certify the results.

Adams had requested further documentation related to the election, ahead of the certification deadline, to confirm accuracy of the results. Fellow county officials denied her request, however, arguing that certification was a mandatory facet of her role and that the request was outside her scope of duties.

Her other colleagues on the panel voted to certify the primary results.

In his ruling, McBurney wrote that nothing in Georgia law gives county election officials the authority to determine that fraud has occurred or what should be done about it.

Instead, he wrote, the law says a county election official’s “concerns about fraud or systemic error are to be noted and shared with the appropriate authorities but they are not a basis for a superintendent to decline to certify.”

Georgia, a swing state that President Biden won by less than 1% in 2020, is a hotbed for election lawsuits as Republican and Democratic officials battle over voter access and election security there and in other battlegrounds.

There are multiple lawsuits challenging a new measure passed by the State Board of Elections that would require county officials to hand-count ballots after they are tabulated by a machine on election night.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.